tl;dr: Most NDAs in are harmful to my business and most importantly bad for my clients. Please don’t take offence if I don’t sign yours.

Like many others who work in freelance software development I am frequently asked to sign NDAs. As with employment contracts, these are seen by many as a formality and the expectation is that they are signed without reading and without question (which is of course a very bad idea). My refusal to sign NDAs has raised more than a few eyebrows over the course of my career, but in almost every case the client accepted my reasons once explained.

Like many others who work in freelance software development I am frequently asked to sign NDAs. As with employment contracts, these are seen by many as a formality and the expectation is that they are signed without reading and without question (which is of course a very bad idea). My refusal to sign NDAs has raised more than a few eyebrows over the course of my career, but in almost every case the client accepted my reasons once explained.

Over on his blog, John Larson goes in to far more detail that I am as to the reasons why he won’t sign a NDA (well worth a read btw). Suffice it to say, my not signing your NDA is not personal, its not me being confrontational, or about me standing up for some abstract principle of software freedom, and it’s certainly not about me wanting to run off with your idea!

Simply, it’s about wanting to preserve the ability to help present and future clients and, in short, maintain the ability to operate a business. Let me explain…

Everything is connected

You have a fantastic idea burning in your brain that you need my help and advice to build. Gosh, I’m flattered! However, I absolutely guarantee that no matter how unique and original the idea or service is, I will be able to name at least half a dozen other services that do, at least in part, something similar. There is a very good chance (especially if your venture is in the realm of web technology and social software) that I have built or worked on something very similar in the past, which may well be why you’re talking to me in the first place!

From a technology point of view, I give a cast iron guarantee that even if the concept is so radical as to have nothing even remotely similar already out there, it will employ techniques and technologies found in wide use. Technology is a field where techniques, ideas and concepts are remixed constantly and overlap widely. As John points out in his essay, the impossibility of tracing the exact time and place a given idea or concept originated leads to a grey area over what one can or can’t use in the future, and can lead to costly litigation.

As an aside, historically, ideas haven’t counted for much in the grand scheme of things, it is execution that matters. The idea of a social network existed long before Facebook, search engines existed long before Google, and Microsoft had a tablet PC long before Apple. In each case, the it was the winner’s execution of the idea that won the day.

That does not mean that your idea is a bad one, or that it is not worth doing, just that the protection of it through legal means by limiting my ability to best help my clients (including you) is probably not where you want to invest your energies. You had the idea so there is every possibility that someone could come up with a similar one in isolation, but that doesn’t meant they’ll implement it well, if at all.

Experience is my business

An agreement which places restrictions on using techniques developed and experience gained on previous projects directly harms my ability to build on my expertise and to inform future design decisions. This directly limits my ability to operate a business.

Too often, the NDA that I am asked to sign (often before discussing a project in detail) restricts the use of anything learnt while working on the project. This is typical for the boiler plate NDA the majority of people seem to use. Even if such mental compartmentalisation were humanly possible, it would mean, at best, reinventing the wheel for each client. Since this is of course impossible, signing such an agreement is knowingly disingenuous.

Put it this way; as my client you are paying for my expertise and experience. How comfortable would it make you feel if you thought that a previous client’s NDA might prevent me from avoiding costly mistakes, advising you on what did or didn’t work in the past, or building something to the best of my ability?

NDAs I can sign

NDAs do have their place, and I have signed them in the past. However, those that I have signed have always covered very specific enumerated and tangible items of declared confidential information.

So for example, if the project requires me to have access to the inner workings of a certain piece of pre-existing patented technology, I would probably sign. Or, if you needed to release to me a client list or a database containing confidential information. Not a problem.

This and much more, I believe, is covered by the principle of client confidentiality; like a doctor, I’m not going to discuss the details of a client’s project with the wider world, unless they have given me permission to do so. If the client wishes to have some extra formality in this regard then I am generally happy to provide it.

However, if the NDA places restrictions on my ability to use my experience to help other clients. I almost certainly won’t be able to sign. Again, like a doctor, I need to be able to use experience to diagnose symptoms and treat them with techniques I’ve used before. My business and my clients can’t afford to have that ability restricted.

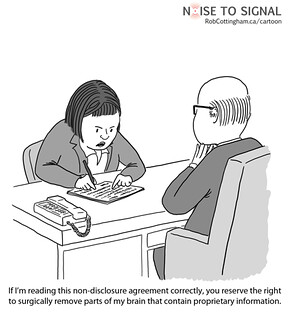

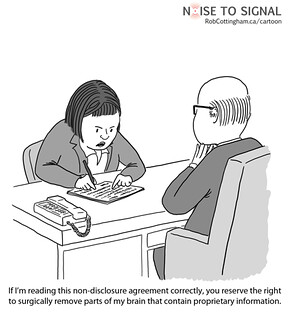

Image “Ssh! It’s a secret!” by RobCottingham used under the Creative Commons Licence.

It has been a few weeks since I finally received my Raspberry Pi, but up until today I have been too busy to play with it.

It has been a few weeks since I finally received my Raspberry Pi, but up until today I have been too busy to play with it.

Like many others who work in freelance software development I am frequently asked to sign NDAs. As with employment contracts, these are seen by many as a formality and the expectation is that they are signed without reading and without question (which is of course a very bad idea). My refusal to sign NDAs has raised more than a few eyebrows over the course of my career, but in almost every case the client accepted my reasons once explained.

Like many others who work in freelance software development I am frequently asked to sign NDAs. As with employment contracts, these are seen by many as a formality and the expectation is that they are signed without reading and without question (which is of course a very bad idea). My refusal to sign NDAs has raised more than a few eyebrows over the course of my career, but in almost every case the client accepted my reasons once explained.  One of the features most requested by NPPL Pilot logbook users was the ability to be able to manage their logbook entries on the move.

One of the features most requested by NPPL Pilot logbook users was the ability to be able to manage their logbook entries on the move.